Mueller Frustrates Both Parties by Rarely Straying From His Report

“I’ll refer you to the report on that.”

“That’s accurate based on what’s in the report.”

“I don’t want to wade in those waters.”

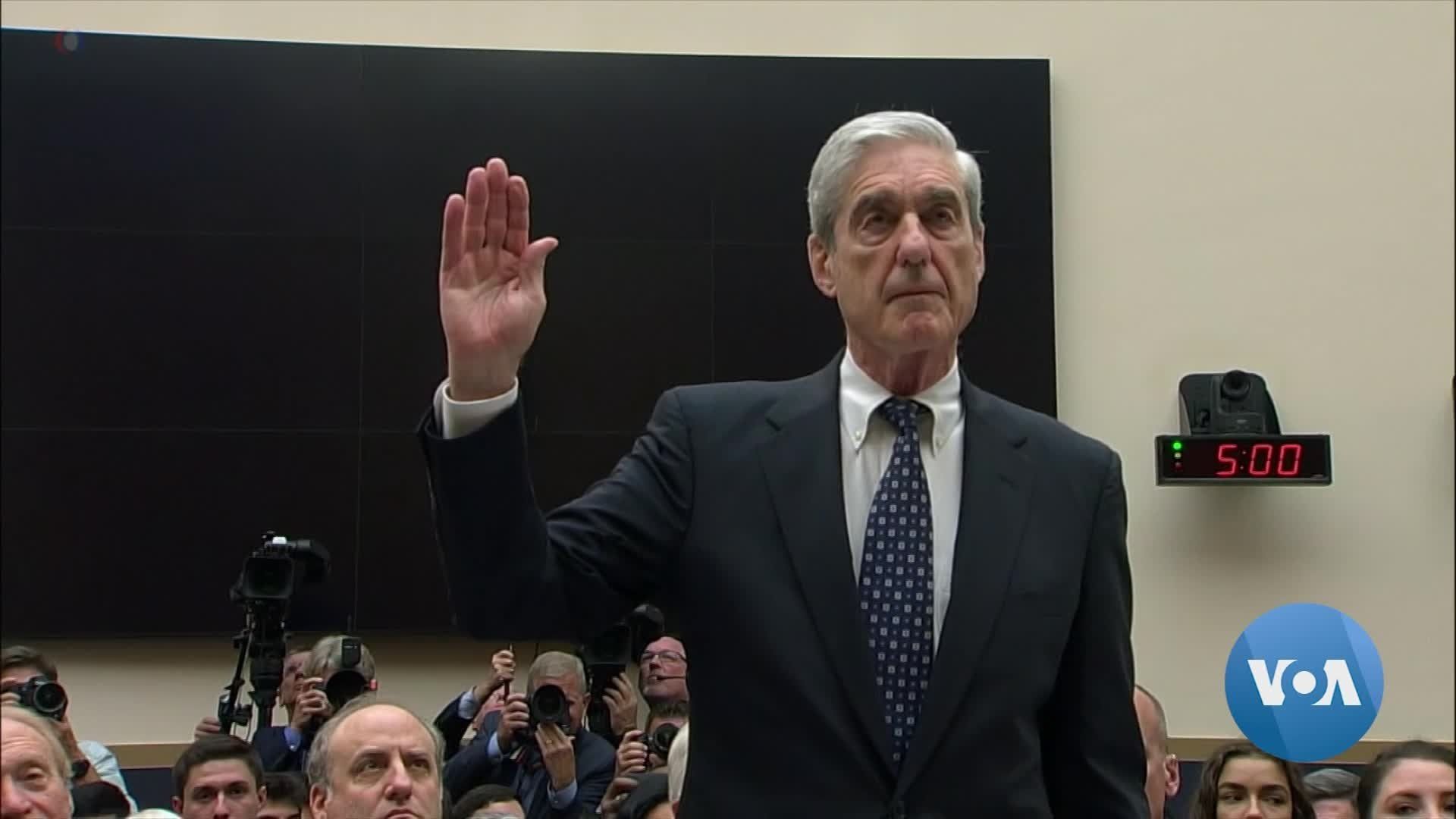

So it went for more than five hours as former special counsel Robert Mueller appeared before two congressional committees Wednesday to testify about his investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and alleged presidential obstruction of justice, closely hewing to a final report he submitted to Attorney General William Barr in March.

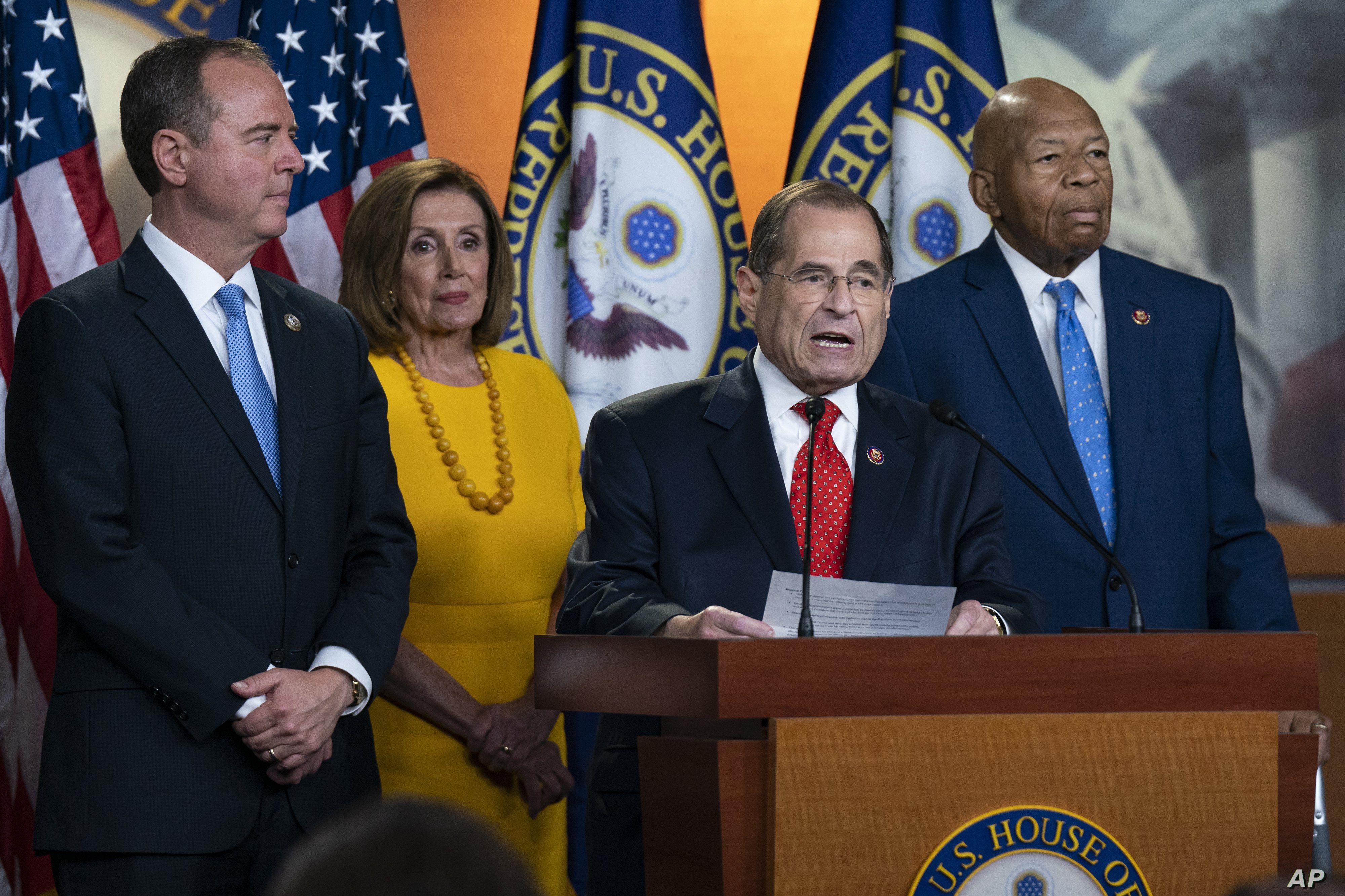

Ahead of his appearance before the House judiciary and intelligence committees, Mueller, a former FBI director, had warned that he’d not stray beyond his 448-page legal thicket. He stuck to his word, frustrating both Democrats and Republicans in the process.

Differing outcomes

Democrats had hoped the public would hear from the special counsel himself damning details of misdeeds by President Donald Trump. With Mueller clearly unwilling to deliver, they were forced to read portions of the report for him, robbing the hearings of the power of a compelling witness’s words.

Republicans wanted to focus the testimony on the origins of a “witch hunt” based on bogus testimony. But Mueller made clear at the outset that he would not answer questions about how the investigation got started in 2016 — months before his appointment as special counsel — and what role the so-called Steele dossier, a largely debunked report claiming ties between Trump and Russia, played in it.

The result was a pair of hearings that elicited little fresh information that the public didn’t already have.

A typical exchange came early during Mueller’s testimony before the judiciary committee between Mueller and committee chairman Jerrold Nadler, a New York Democrat:

Nadler: “Director Mueller, the president has repeatedly said that report completely and totally exonerated him. But that is not what your report said, is it?

Mueller: Correct. That is not what the report said.

Nadler: I’m reading from Page 2 of Volume 2 of your report. It’s on the screen. You wrote: “If we had confidence after a thorough investigation of the facts that the President clearly did not commit obstruction of justice, we would so state. Based on the facts and the applicable legal standards, however, we are unable to reach that judgment.” Does that say there was no obstruction?

Mueller: No.

The Democrats, and to a lesser extent the Republicans, followed the same formula during both hearings.

In the judiciary committee, the Democrats took turns highlighting five episodes of potential obstruction of justice by Trump, ranging from the president’s attempt to have the special counsel removed, to his “efforts to encourage witnesses not to cooperate with the investigation.” In the intelligence panel, they enumerated extensive contacts between the Trump campaign and Russia during the 2016 election, even though Mueller found no evidence of a criminal conspiracy.

Nothing new

In the end, much to their frustration, Mueller said virtually nothing new as he paused, hesitated, and at times asked members to restate their questions or cite the page number. When a member appeared to be directly quoting from the report, the special counsel would simply offer, “If it’s in the report, it’s accurate.” And if he thought a member was mischaracterizing the report, he’d respond, “I’d not subscribe to that characterization.”

Jessica Levinson, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, said Mueller’s reticence took the drama out of the hearings.

“Today was not really about fact-finding. It was about the drama,” she said. “And when Robert Mueller’s answers are all some version of ‘Yes, no, or look at the report,’ it completely takes the air out of the room. It takes any drama out.”

Mueller concluded his 22-month investigation of Russian election interference in March. In his final report, he wrote that he found little evidence that the Trump campaign had conspired with Russia to influence the outcome of the 2016 election.

But he left undetermined the question of whether Trump could be charged with obstruction of justice, citing a long-standing Justice Department policy that says a sitting president can’t be indicted, and writing that the U.S. Constitution offers a separate process for dealing with presidential offenses.

Mueller Capitol Hill Testimony Deepens Political Divide video player. Embed" />Copy

Mueller Capitol Hill Testimony Deepens Political Divide video player. Embed" />CopyStayed out of the fray

Many Democrats wanted to use the hearings to discuss impeachment, but Mueller refused to be drawn into it, carefully avoiding the word even when it was pointed out to him that he had used it in his own report. And when several Republicans harshly criticized him for refusing to “exonerate” the president of obstruction of justice, he offered little in his own defense.

Levinson said the hearings gave Democrats little to make the case for impeaching the president.

“I think if we look at today, people are thinking, ‘I can’t imagine this Congress conducting impeachment proceedings,’” Levinson said.

The only time Mueller pushed back against critics was when Republicans renewed old accusations that most of the 19 lawyers on Mueller’s former team included Democrats who had contributed money to Hillary Clinton’s campaign.

“We strove to hire individuals who could do the job,” he said. “What I care about is the capacity of the individual to do the job, and do the job seriously and quickly and with integrity.

He also strongly disputed the claim his investigation of Russian interference in a U.S. election was a “witch hunt,” and warned that the Russians will try again to undermine the American political system. He stressed the need for U.S. intelligence agencies to work together to protect U.S. elections from foreign adversaries.

Trump Vetoes Congressional Effort to Block Saudi Arms Sales Next PostPresident Sees ‘Very Good Day’ for Him in Mueller Testimony

Trump Vetoes Congressional Effort to Block Saudi Arms Sales Next PostPresident Sees ‘Very Good Day’ for Him in Mueller Testimony